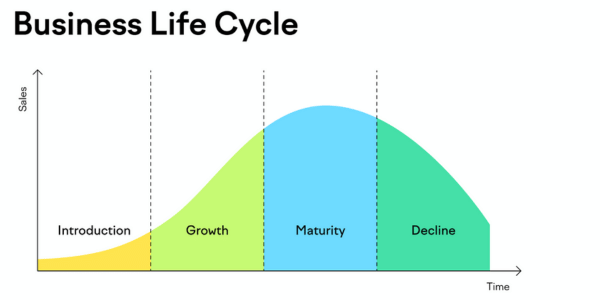

Similar to living organisms, companies undergo distinct life cycles. Comprehending the corporate lifecycle assists investors in making judicious decisions regarding stock purchase, retention, or divestment. Perpetually holding a stock without considering the evolving dynamics of the company can impede long-term financial gains. While certain companies may prosper over extended periods, even well-managed firms will inevitably encounter challenges that can diminish their worth. This highlights why maintaining a stock indefinitely is not a viable investment strategy.

The Corporate Lifecycle Explained

Business entities, akin to human life cycles, progress through distinct stages during their operational tenure. These stages are:

1. Startup Stage (Birth)

2. Growth Stage (Youth)

3. Maturity Stage (Adulthood)

4. Decline Stage (Old Age)

Each stage possesses unique attributes, necessitating a tailored approach from investors.

Startup Stage (Birth)

This phase denotes the inception of a company, often marked by pioneering products, disruptive concepts, and high growth prospects. These enterprises typically operate at a loss and rely on external funding. The associated risks are considerable due to limited market traction and untested business models, but so are the potential rewards. Investors may realize exponential returns from stocks in the startup stage if the company prospers. However, the risk of failure is significant, accompanied by substantial volatility. At NeuralBahn, we refrain from investing in start-ups and IPOs. Instead, we adopt a strategy of awaiting market confirmation of the conclusion of the start-up stage lifecycle before conducting stock analysis and assigning ratings.

Growth Stage (Youth)

Upon achieving a product-market fit and commencing consistent revenue generation, companies transition into the growth phase. During this period, firms prioritize operational expansion, broadening their customer base, and augmenting market share. Although profitability improves, a substantial portion of earnings is reinvested into growth initiatives. This phase often presents an opportune moment for investors. Stocks in this stage can yield substantial returns while mitigating some of the risks inherent in the startup phase. Growth stocks are particularly favored during this juncture as companies retain room for expansion.

Maturity Stage (Adulthood)

Following years of expansion, companies eventually encounter a phase where growth decelerates. Market saturation, heightened competition, and reduced innovative capacity typify this stage. Entities in the maturity stage consistently generate profits and often distribute dividends to shareholders, given limited reinvestment prospects. Mature companies typically offer diminished returns compared to the growth phase. For investors, this period signifies stability and dividend income, but concurrently warrants a review of prospective risks.

Decline Stage (Old Age)

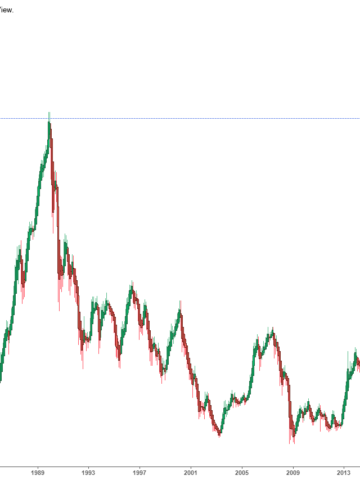

No company perpetually maintains its peak position. In the decline stage, enterprises contend with stagnation, disruptive competitors, market saturation, or obsolete business models. Revenues may shrink, profits dwindle, and stock prices tend to underperform. Formerly dominant firms such as Kodak and Blockbuster succumbed to rapid technological advancements and market shifts, leading to irreversible decline. At this juncture, it becomes imperative for investors to reassess their position. Retaining stocks of companies in decline can precipitate substantial losses.

The concept of purchasing and retaining a stock indefinitely may appear attractive, particularly for blue-chip companies, but it overlooks the dynamic nature of markets and companies. There are several factors that make holding a stock indefinitely risky:

1. Market Disruption:

Technological advancements, changes in consumer preferences, and the emergence of new competitors can disrupt even the most well-established companies.

2. Economic Cycles:

Recessions, inflation, or alterations in global trade policies can significantly impact industries and the companies within them.

3. Management Changes:

A change in leadership, corporate governance issues, or a shift in strategic focus can either invigorate or erode value. It is essential for investors to monitor how these changes affect long-term growth and profitability.

4. Industry Saturation:

Even if a company continues to perform well, it may reach a point of saturation in a highly competitive and saturated industry.

5. Regulatory and Environmental Factors:

Changes in regulations, geopolitical dynamics, or environmental constraints can create challenges that impede or reverse a company’s growth.

When to Exit a Stock:

Understanding a company's life cycle assists investors in making timely decisions on when to exit a position. Some indicators that it may be time to sell include: - Earnings Declines - Strategic Missteps - Technological Disruption - Shrinking Dividends. While no universal rule dictates when to exit, remaining well-informed about a company’s life cycle and the market conditions surrounding it is crucial for safeguarding long-term returns.

The notion of indefinitely holding a stock is alluring but not feasible. Similar to individuals, companies experience periods of growth, stability, and decline. Clinging to a stock without acknowledging the indications of the company's position in its lifecycle can result in reduced returns or even losses. A prudent investor should routinely assess each company, remain vigilant to market fluctuations, and be ready to divest when a company's prime has passed. The essential approach is to maintain adaptability, ensuring that your portfolio reflects both market realities and the inevitable transformations encountered by companies.

Gain valuable insights into your equity portfolio with our research reports. Contact aaron@neuralbahn.com to take your investment strategy to the next level.

www.neuralbahn.com